In Greek papyri from Egypt, we find two standard meals: the ariston and the deipnon. These daily meals were eaten in this order and are hence conventionally translated as ‘lunch’ and ‘dinner’. Dictionaries will also give the option of translating ariston as ‘breakfast’, but this mostly refers to the early archaic period, when the ariston was eaten in the early morning and the deipnon at midday. Meaning had shifted by the end of the archaic period, however, just as the French déjeuner (litt. ‘breaking the fast’) once referred to breakfast but now means lunch. All papyrological evidence long postdates this shift in meaning.

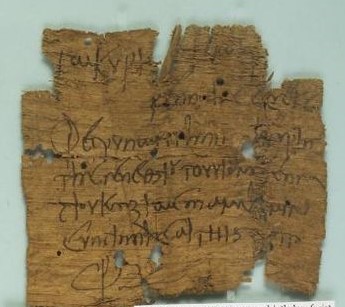

In this blog, I want to focus on these meals in an account from the fifth century CE: P. Wash. Univ. II 98. This short document lists the daily expenditure of wine for consecutive days. I copy here the text of lines 5-7 from the edition (the only lines specifying meals) and translate them:

β εἰς ἄρ(ιστον) δῖπν(ον) δι(πλᾶ) β

γ εἰς ἄριστο(ν) δῖπνο̣ν δι(πλᾶ) β

εἰς δῖπνον̣ δι(πλοῦν) α

Day 2: for ariston (and) deipnon: 2 jars

Day 3: for ariston (and) deipnon: 2 jars; for deipnon: 1 jar

The observant reader may find something odd: why would the accountant give a combined amount of wine for lunch and dinner for day 3 and then an additional amount for dinner on the same day? The more logical practice would be to either separate the count for each meal, or to give only a combined amount.

The problem lies, I think, not with the accountant, but with the reading. The scribe wrote ‘ar. dipn.’ for day 2 and ‘aristodipn.’ for day 3: for each point in the transcription there is an abbreviation sign in Greek. There is no additional abbreviation mark suggesting the ‘and’ implied by the text of the edition. Therefore, I think that on both days, jars of wine were in fact served with an aristodeipnon, a ‘dinner eaten at lunchtime’.

© Princeton University Library, original at https://dpul.princeton.edu/papyri/catalog/gb19f931j

The term aristodeipnon is extremely rare, but not out of place in a late-antique context. It is also attested in the chronicle of Malalas (18.474 (71)); he mentions an aristodeipnon for military heroes hosted on 13 January, 532 CE by emperor Justinian in his palace. Further confirmation that ‘dinners at lunchtime’ also make sense in the context of fifth-century Egypt is provided by P. Oxy. IX 1214. This is an invitation to ‘dine’ at the seventh hour, that is very shortly after midday and thus too early for a normal elite deipnon – served at the ninth hour in the high Empire, but moving somewhat later again in late antiquity.

The temporary fashion of aristodeipna or ‘dinners at lunchtime’ fits in the context of a late-antique overhaul in meal times. Up until the fourth century, the deipnon was the standard ‘main meal’. Public banquets, an important aspect of sociability in the ancient world, always revolved around the deipnon. In an upcoming article on the temporality of meals in Roman and late-antique Egypt, I argue that, from the fourth century onward, the ariston accrued a social function as well. At the same time, important features of the culture of commensality connected to the deipnon declined in the fourth century, as the cult associations which had organized public banquets disappeared, as did many festivals which had featured them. Other scholars, such as Hudson, have already argued that the end of public banquets coincided with a transformation if HOW people dined, namely with a decline of eating while reclining on couches. I would like to add that it also changed WHEN people dined. From the fifth century on, the ariston became the main meal. In late-antique papyri, it would therefore be more accurate to translate ariston and deipnon as ‘dinner’ and ‘supper’ than as ‘lunch’ and ‘dinner’. Aristodeipna belonged to the intermediate phase in which the ariston had in practice already become the main meal, but people still remembered that to banquet was ‘to eat deipnon’. Once this faded from living memory, the combined word aristodeipnon once again became unnecessary.

Sofie Remijsen

References:

Sofie Remijsen, ‘Lunch and Dinner? The Temporality of Meals in Roman and Late-Antique Egypt’, forthcoming.

Hudson, Nicholas. Dining at the End of Antiquity. Class, Status, and Identity at Roman Tables. University of California Press, 2024.