The Muslim expansion of the 7th century turned the Ancient World upside down. Less than 30 years after the death of their Prophet, Muslims from Arabia ruled over much of what had been the Eastern Roman and Sassanian empires. But what did this mean for the average person of the day? How did the rule of the new masters affect their habits and prospects (if at all)?

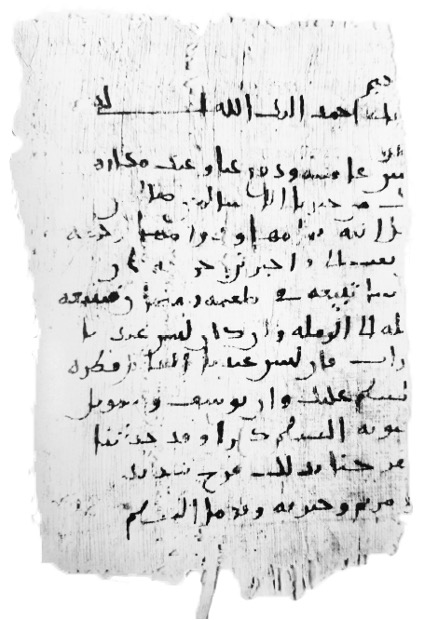

Overall, we know very little of how the rise of Islam influenced the daily grind of your average 7th-and 8th-century Joe. Fortunately, some light is shed onto these kinds of questions by texts such as the one shown here. This is a papyrus written in Arabic, found in the town of Ḫirbat al-Mird (the ancient Hyrcania; ca. 20 km east of Jerusalem). It is the left half of a letter written just about 100 years after the Arab conquest. Texts such as this one are quite different from chronicles and literary works we base most of our understanding of antiquity and the pre-modern age on. Rather than talking of battles and treaties, they tell us simpler stories. But it is surprising how much one can learn from even a single fragmentary document.

From our example, for instance, we learn about the exchange of a food-merchant (the writer) and a business partner (the recipient). In the text, the writer asks his associate if he has any “food of Ramadan” and “food and drinks for the breaking of the fast”(fiṭr in Arabic)to sell. What we have here is in all probability one of, if not the earliest references to the festival of the ʿĪd al-Fiṭr (“feast of the breaking of the fast”), the Muslim holiday that marks the end of the sacred month of Ramadan. To this day, the Feast remains a joyous occasion in which Muslims gather together for prayer and (more to the point of the papyrus) to celebrate the end of the fasting period by eating food and sweets.

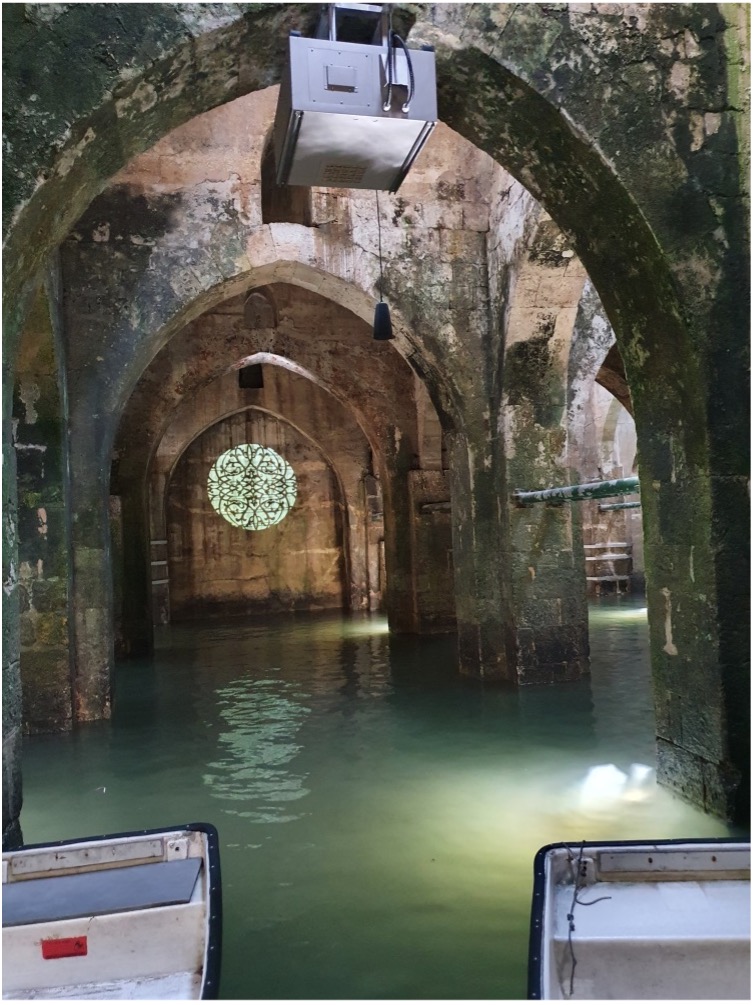

For more earthly minded businessmen such as the writer of our letter the celebrations of the Feast also presented an unmissable opportunity. Our writer’s nose for business becomes apparent in the next paragraph of the letter, when he instructs his partner to send what he has or go himself (the text is not clear) to the nearby city of Ramla. This was the new capital founded by the governor of Palestine (and future caliph) Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik, the early Islamic ruins of which are still visible today. It is possible that our dynamic duo expected to find not only a higher concentration of buyers there (Muslims were, after all, still only a minority of the total population at that time) but also to encounter a wealthier clientele of Muslim magnates and courtiers.

We do not know much about the protagonists of the letter beyond their profession (not even their names in fact!). Towards the end of the letter, our writer uses the occasion to ask his partner to greet a few dear ones back home on his behalf. Since all the persons mentioned in the greetings, as well as a third business associate, carry typically Christian and Jewish names (Samuel, Joseph, Mary, Tomas, and George), it is quite possible that our protagonists were not Muslims themselves.

This tiny snapshot from the distant past (and many more similar ones with it) gives us an unparalleled opportunity to peek behind the curtains of historical events. It appears that only a few generations after the Arab conquest, the newly introduced Muslim holidays were becoming a hub for multireligious encounters. The fact that the correspondents of our letter wrote in Arabic suggests that they had assimilated to some degree into Arab culture and society. What is more, we see how the introduction of Muslim festivals had a way of setting rhythms of everyday business beyond Muslim circles – not unlike how Christmas holidays continue to shape general family and shopping habits in Christian-majority countries!

Eugenio Garosi