In the project database conversions of dating formulae in edited texts are automatically checked against extensive chronological tables. This process occasionally brings to light calculation errors in leap years or discrepancies based on an outdated understanding of when the indiction year started, which has resulted in an article with corrected dates for Coptic documents and tombstones by Sofie Remijsen and myself (2023). In a previous blog, I proposed an earlier year of death for Bishop Pesynthios of Koptos. The present blog focusses on the date of a festive ceremony following the renovation of the church at the Monastery of Pbow, the main monastery of the koinonia founded by Pahom (better known as Pachomius). After the second enlargement of the church in the second half of the fifth century, it was dedicated to Pahom, who was by then commemorated as a saint.

The dating of the event to 459 CE is based on A. van Lantschoot’s combined reading of two passages in the Arabic version of a homily attributed to Timothy II Aelurus, anti-Chalcedonian Patriarch of Alexandria (457-460, 475-477). He converted one of the mentioned dates – Saturday Hathor 11 – to November 7 (the usual Julian day in a common year) and found out that November 7 fell on a Saturday in 459. The problem is that once every four years, November 7 equals Hathor 10, because the leap day is introduced in the Egyptian calendar six months before it is introduced in the Julian calendar. Consequently, Hathor 11 in 459 actually corresponds to Sunday November 8, which makes it necessary to look for another date that matches all the details. Here, the chronological information in the Lived Time project database comes in handy. For this reason, this blog briefly discusses the relevant passages in the sermon, clarifies Van Lantschoot’s argument for accepting Patriarch Timothy’s period of office as the likely timeframe and proposes alternative dates.

The homily on the Church of Pahom is partly preserved in Sahidic, but the details mentioned above only appear in a complete Arabic manuscript, Vatican arabe 172, which is dated by a colophon to 1345 CE. Van Lantschoot published the text together with a French translation (pp. 26-56). The text is presented as a homily to be delivered on Pahom’s feast day, i.e. Pachons 14, which corresponds to May 22 in common years (see fol. 105b).

The first relevant passage appears in the introduction (fol. 99a): “This dedication took place on the fifteenth of the month Hathor”. The second one describes a meeting between Patriarch Timothy and abbot Martyrios at the Monastery of Pbow on “Saturday, Hathor 11” (fol. 106a). The former proposed to consecrate the renewed church the next day, on the feast day of the Archangel Michael (Hathor 12), but that night, an angel appeared and told him to wait until Hathor 15.

The ceremony is set at the time of Emperor Leo I (457-474; fol. 103b), Patriarch Timothy II and Abbot Martyrios, who finished the renovation of the church that one of his predecessors, Victor (attested in 431), had started. Van Lantschoot (pp. 16-17) observes that the attribution of the sermon to Patriarch Timothy is unlikely, for the many references to the Pachomian tradition and the use of literary devices to glorify the church at Pbow indicate that the sermon was composed by a Pachomian monk. However, he accepts Timothy’s period of office as the timeframe within which the event took place, arguing that the association with this patriarch instead of a successor or predecessor must have historical significance (pp. 20-21). In general, the dedication of a church is such an important event – particularly in a monastic context – that it is celebrated with an annual feast, resulting in a tradition in which historical details are repeated every year (p. 22). The mention of Emperor Leo I supports a date in the period 457-474 as well. According to the sermon, Abbot Martyrios contacted him shortly after his ascension to the throne, when the imperial measures against the anti-Chalcedonian church of Alexandria ceased, which suggests a date around 460.

On the basis of the two passages, Van Lantschoot concluded that the ceremony took place on November 11 (the usual Julian day coinciding with Hathor 15 in common years) and that Hathor 11, or November 7, fell on a Saturday in 459, which fits with Patriarch Timothy’s chronology: in January 460, he was exiled to Gangra (in modern Turkey), on account of his alleged complicity to the violent death of Proterius, the Chalcedonian Patriarch of Alexandria. Van Lantschoot did not check for other possible dates, for instance, in the period after Timothy’s return to Alexandria (475-477). Later scholars explicitly mention 459 as the year in which the church in Pbow was dedicated, notably S. Timm (1984, 949) and P. Grossmann (1991, 1928; 2002, 60 and 552).

However, since Saturday November 7, 459 was actually Hathor 10, we should look for alternative dates. Within the period 457-777, Hathor 11 fell on a Saturday in 464, 470 and 475. Consequently, the dedication on Hathor 15 possibly took place on Wednesday November 11, 464 or 470, or on November 12, 475. At first glance, the third date seems preferable, for it coincides with Patriarch Timothy’s later years, when he could have travelled to Pbow, but it was Emperor Basiliskos (475-476) who allowed him to return, whereas the sermon links the ceremony to Emperor Leo I.

In that case, 464 is more likely (closest to the date when Abbot Martyrios supposedly contacted Emperor Leo I), even if it means that Patriarch Timothy could not be physically present during the festivities. In fact, his presence was not required, since the bishop of Nitentori (Dendera) could oversee ceremonies in his diocese, but the composer of the sermon wanted to emphasise the importance of the church at Pbow and that of the anti-Chalcedonian Church. Therefore, he took much poetical licence, stating that the monastic church was already blessed by Jesus Christ on the eve of the dedication and that 824 bishops from Egypt and abroad attended the festivities.

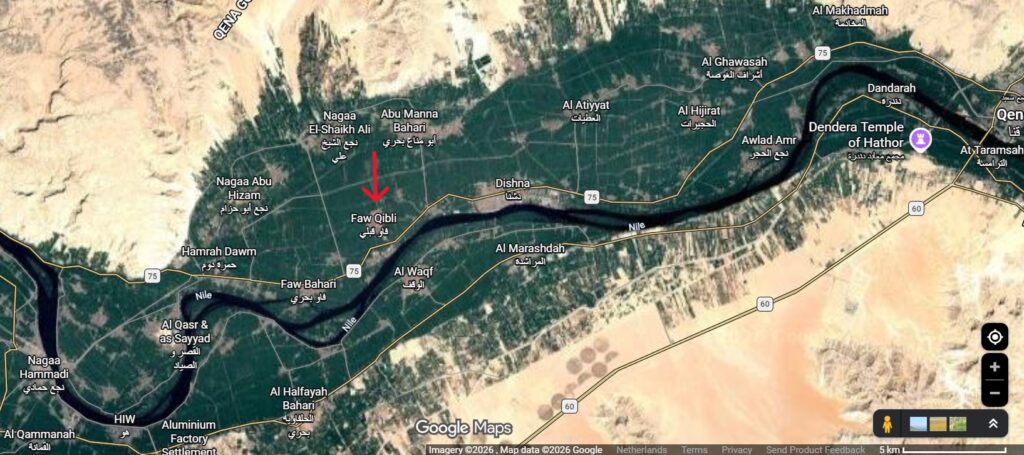

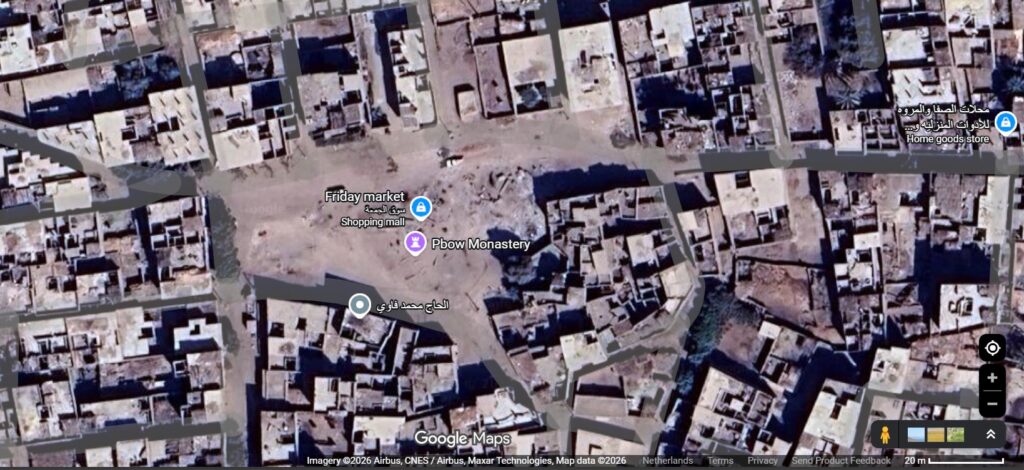

Although the most likely alternative date – November 11, 464 – is hypothetical, the revision is significant for three reasons. Firstly, it demonstrates the value of a date checking tool or perpetual calendar (Bagnall and Worp 2004, 171) for the conversion of dates including a weekday, for any proposed date is likely to be repeated without being checked. Secondly, a slightly later date for Abbot Martyrios affects the chronology of the Pachomian leaders at Pbow and the Pachomian koinonia in general. Lastly, the date is relevant for the history of a building that no longer exists today. P. Grossmann, who has published ground plans showing the three building phases of the church, connects the dedication ceremony to the third phase, when the enlarged church measured 75 × 37.5 m (pp. 59-60, 551-552, Fig. 163). The remains of this monumental building, including granite columns and capitals, now lie scattered in an open space between the houses of the modern village of Faw al-Qibli, where the market is held on Fridays (Figs 1 and 2).

Renate Dekker

Fig. 1 The area of Faw al-Qibli (Google Maps)

Fig. 2 View on the remains of the church (Google Maps)

Bibliography

- Grossmann, P. 1991. ‘Pbow: Archaeology’, in: A.S. Atiya (ed.), The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 6, New York, 1927-1929 (online).

- Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, Leiden.

- van Lantschoot, A., ‘Allocution de Timothée d’Alexandrie prononcée à l’occasion de la dédicace de l’église de Pachôme à Pboou’, Le Muséon 47 (1934), 13-56 (online).

- Spanel, D.B. 1991, ‘Timothy II Aelurus’, in: A.S. Atiya (ed.), The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 7, New York, 2263-2268 (online).

- Timm, S. 1984. Das christlich-koptische Ägypten in arabischer Zeit, vol. 2, Wiesbaden, 947-957.